Monira Al Qadiri Taps Culture and Mythology in ‘Holy Quarter’

The exhibition is on view until December 23 at the SCAD Museum of Art in Savannah, Georgia.

Image courtesy of SCAD and Monira Al Qadiri.

Multidisciplinary artist Monira Al Qadiri has always been connected to her cultural roots and history in the Persian Gulf. Whether it’s mythology or the lands’ resources, Al Qadiri has dedicated much of her work to dissecting the region’s complex yet rich past that has led these lands to where they are today.

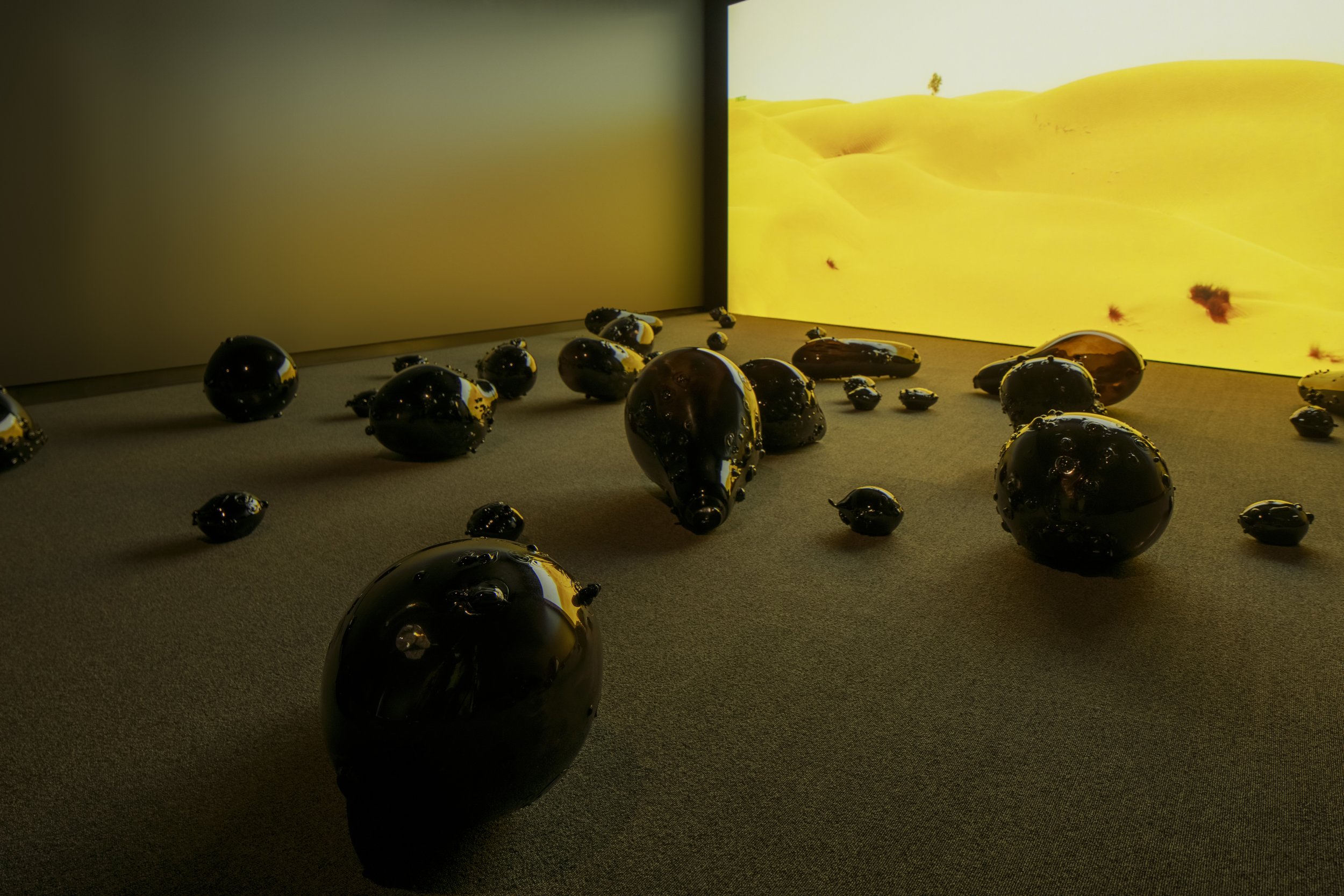

Holy Quarter, a film and sculptural installation, expands on these themes of Al Qadiri’s geographical heritage and is now on view until December 23 at the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) Museum of Art. The film and sculptural installation give viewers a feel of all the sensories. As you walk into the gallery, you’re met with Al Qadiri’s recreation of the Wabar Pearls in the large photo of her nine-foot, glass-blown sculptures placed in Oman, where Holy Quarter was achieved.

Further inside is a film created by Al Qadiri displaying Oman’s Mars-like nature and elements. An AI spirit of the meteor narrates the film, warning viewers of the ecological risks of human actions. A sci-fi music composition created by Al Qadiri’s longtime collaborator and sister, Fatima Al Qadiri, perfectly encaptures the otherworldly, ethereal nature of the Arabian Desert in Oman.

According to mythology, British explorer Harry St. John Philby ventured into the vast Empty Quarter desert searching for the ancient city Atlantis of the Sands. What once was a thriving city with resources, palaces, and castles, a rumored divine punishment left the city destroyed. All that was left was the black burnt pearls of the women who lived there.

However, no ancient city—or even ruins—was in sight when Philby arrived. Instead, he discovered large craters with shiny black bead-like objects on the ground. After analyzing them with the British Museum, he learned that they were the remains of a meteorite. He found them in Ubar but mispronounced the name of the desert and named the remains Wabar Pearls. This inspired Al Qadiri to design them to scale, titling them W.A.B.A.R.

Al Qadiri spoke with 1202 MAGAZINE in SCAD’s iconic Poetter Hall to discuss what the land of the Persian Gulf means to her, the creative process behind Holy Quarter, and how her continuous themes and motifs play a part in her everyday life.

Why did you choose to dedicate Holy Quarter to Harry St. John Philby?

I came across this interesting story about the Empty Quarter Desert, which is the biggest contiguous desert in the world between Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Oman, and Yemen. It’s actually bigger than France. In the 1930s, this British explorer went to an empty corridor looking for the ruins of an ancient city because he heard a story about ruins in the middle of the desert, and if he found them, he’d be a famous archaeologist. At the time, an archaeological boom was happening everywhere. Everybody wanted to be the next big thing, especially the Brits.

The 1930s is pretty recent. I thought this would be a much older story.

Exactly, it was less than 100 years ago. He manages to get there and convinces the locals to take him. He wears an Arab garb and calls himself Abdullah. They take him to the desert with camels, and the camels die along the way. He finally gets to this spot, sees huge craters, and is extremely disappointed that there is no city. He thought there were volcanoes, but they told him it was the outskirts of the city gates. There are beautiful, black beads all over the ground, and they say they were pearl necklaces of the ladies that used to live there, but the people were so decadent that God punished them and burned everything down. So, all that’s left are the craters and the pearl necklaces.

Is this a true story or mythology?

It’s a real story, but it’s also mythology. He’s (Philby) so disappointed. He thinks this is some volcanic lava, so he takes the samples back to London’s British Museum to check what the black beads are. Lo and behold, his friend tells him it’s a meteor from outer space. I thought it was so amazing. I work a lot on the subject of pearls because my family history involves pearls. In Kuwait, the main industry before oil for 2,000 years was pearl diving. After oil, it disappeared. So, I’m always trying to think about the pearls in my work as a disappeared cultural heritage.

Are pearls still prevalent in Kuwait?

No, they make a fake heritage out of it now; they tell you it’s your history, but it feels like a Disney movie. They make it sound like a tourist attraction. It’s very sterilized. They conveniently erased the most essential part of the story, which is that the people were poor because everybody in that part of the world is super wealthy now. It makes it feel like fiction — like it never happened.

You mentioned you almost died seven times while filming in Oman, and the Secret Service followed you. What happened there?

We went into the desert for about an hour, and our car had already flipped over. The Secret Service followed us and basically saved us. But I was actually glad they were following us. At the time, the war next door in Yemen was really intense, and I had a drone. They didn’t believe I was in this area to only film nature. They would call me from the Ministry of Defense every day about what the film was really about. After the first day of them following us, they saved us and came with us every day. You need permission for everything.

Image courtesy of SCAD and Monira Al Qadiri.

How did you come up with the name W.A.B.A.R. for the sculptures?

It’s the wrong name Philby gave to the pearls. It’s an area where they found the craters called Ubar. He decided that Wabar was much easier. You can actually buy them. I went around to a lot of meteorite hobby shops all over the world, asking about these things. I found some in France, Spain, and Germany. I have a small collection of them — they’re very tiny. Last summer, I was asked to do a public art commission in the desert, and this was the first thing that came to my mind. I needed to bring the pearls back to the desert, but not the size of it. I enlarged them hundreds of times bigger. I wanted to bring back the mythology of the power of the human imagination. You can see a tiny thing in the desert and make it this crazy, fantastical story. I’m also in love with the black, shiny color. It also looks like droplets of oil. I’m also making a social critique about my region. People are so blinded by this substance, and someday, divine punishment will come because of their decadence.

What are the sculptures made of, and how did you make it?

The sculptures for Holy Quarter are made of glass. Because of the real meteorites, they come in with all of this heat and material and mixes with the sand. The actual black holes are made of glass, which is why they shine. I really wanted to remake them out of glass, and it was a very difficult process because blown glass has a certain size you can work with. It also depends on the size of the oven and the weight of it. You have to work really fast. I couldn’t make them because they were too big, so I worked with glassmakers in the Czech Republic who blew up heavy glass, rolled it around in 12 pieces of glass to stick to it, and then fired it. It was a very crazy process. We had so many failed and broken pieces.

They look great! I think the imperfections are what make the sculptures look real and intentional.

Exactly. Even for the professional glassmakers, this was completely experimental. I didn’t know if we were going to be able to do this, but I’m very happy with the results.

Can you also discuss the sound and film elements of Holy Quarter? I know your sister, Fatima Al Qadiri, composed this accidental music that perfectly fits the film's scenery.

I collaborate with my sister on all kinds of soundtracks for any video or film work. I’m in love with her music. We grew up together. It’s the closest music to me as a person. We have the same imagination, but it goes in different directions and muses. I understand her, she understands me. I’m lucky to be able to always work with her. It’s something I always do. She’s the first person I’ll go to for any installation or sound I need to do, and it always turns out perfect.

Why did you choose to film in Oman? Were there any other locations you wanted to film?

No, the whole thing was a crazy experiment. I’d never been to Oman before, so I went straight to the desert. I had a cinematographer and fixer to set up with me who were friends of mine, but they backed out at the last minute. Then I had to work with a cinematographer and fixer who I don’t know. All of us were in Oman for the first time, and I was traveling with people I didn’t even know. But in the end, we became best friends. They’re like my brothers now, and I love them so much. It was a crazy miracle. I thought maybe one or two locations would be nice for this film, but I didn’t expect to see the kind of landscape I saw in so many different places. We had to stop so many times. Everywhere you looked was like another planet. I found out NASA did training there, which is crazy because the landscapes look like Mars. It’s a very naturally rich country. You can see the geological formation of the Arabian Peninsula, which is millions of years old.

How does Holy Quarter feel different from your previous works?

They have a lot more narrative to them, and I like that because my work is very different. I studied in Japan and it was a very hyper-visual culture. I really absorbed that. My work is very hyper-visual. I think the narrative side comes very much from the literary tradition of the Arab world. It’s been a culture of telling stories for thousands and thousands of years. The work merges the two together in a way that’s visual with a narrative structure to understand it.