Review: Neal Vandenbergh’s Vivarium Glass

The exhibition is on view until November 11.

Every day, we put on a mask to face the world. Masks help us gather ourselves in preparation for interactions ranging from pleasant to arduous and everything in between. They help us maintain calm facial composure, signal empathy in mirroring the emotions reflected at us, and sometimes, a mask matches the sinister motives that brew deep beneath the surface.

In Neal Vandenbergh's vivid drawings in his current exhibition, Vivarium Glass at Silke Lindner in New York, faces are obstructed by a second skin covering an underlying horror or mysticism. Inspired by the fantasy conjured in the intangible states of its relationship to reality, Vandenbergh synthesizes social and psychological experiences into scenes that capture the spectrum of faces performed internally and externally. The hallucination of adapting to an ever-evolving reality is exposed, laying bare the horrifying truths that beg to remain concealed.

The raw edges of each drawing are reminiscent of the skin's texture as it peels away from the epidermis, which enhances the blend of human and snake faces and the mutual necessity to shed remnants of our former selves. Malleable materials like graphite and pastel are ideal for depicting the multiple layers of each creature in these drawings, mutating and shifting with the beings emerging from various stages of depth. The veils of pigment illuminate the transfigurations of each mask as the color shift prescribes the emotions developing with a reptile or beneath the guise of a former president. In Hands and Jimmy Carter Mask 1, fingers emerge from the vacant orifices where a human head can see and breathe if shielded in this rubber skin. In a surreal change of placement, two light blue almond eyes hover on the mask's forehead and the assumed face underneath it. What are these serene eyes saying to us? Do they wish for political control? Are they itching to rip off their ideological facade? We are limited in examining each layer. Only imagination can tell their story.

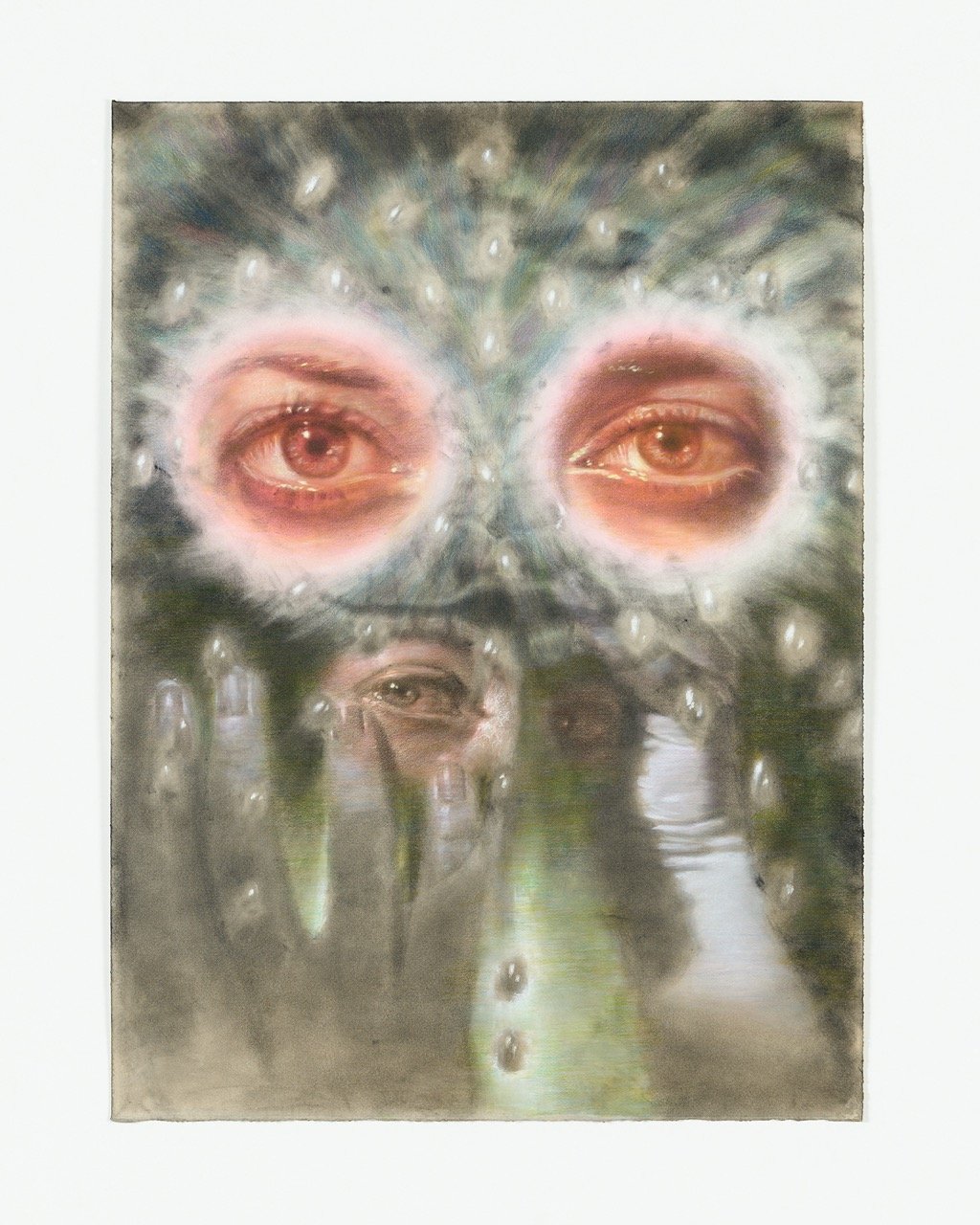

The eyes and windows to each portrait's soul are aglow in vibrant shades of cerulean or soft amber. Snake With Human Eyes 18 is the embodiment of the word sinister. The magnetic hostility emanating from the gaze, paired with a delicious one, holds whoever is looking in its direction captive. A fear washed over that turning to stone was a plausible outcome if engagement with this creature was prolonged. In Hands and Eyes 16 and Hands and Eyes 17, Vandenbergh illustrates fantasy and science fiction magazines' influence on his visual language. The serpentine traits are more evident than those in the other works. The glowing dots indeed indicate that these beings are from another world. These tandem portraits with a radiating right eye express both horror and mysticism as their hands move away from their posed freight into open-palmed allure, all the while the imprint of an initial head grasp lingers.

Snake Mind 14 is utterly cinematic and encompasses the images present throughout the show. Cold grey hands reach up to hold the face belonging to the tense-filled eyes within the brilliant snake. The glowing amber eyes are hypnotic and inviting, which is probably how the being trapped within entered their current predicament. Yet again, another snake enticed a victim into a world of dangerous consequences. The mask, the ultimate tool of deceit, reveals our truth.